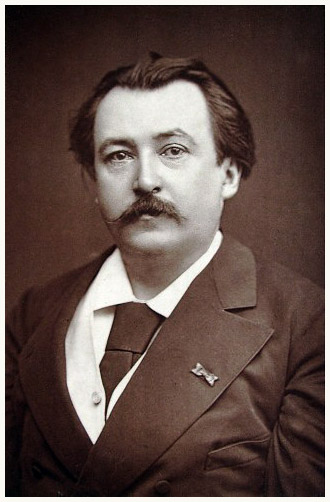

Gustave Doré

It was at the Café de L’Horloge in Paris. Mr. Whistler sat leaning on his cane, looking off into space, dreamily and wearily.

He aroused enough to answer the question:

“Doré—Gustave Doré—an artist? Why, the name sounds familiar! Oh, yes, an illustrator. Ah, now I understand; but there is a difference between an artist and an illustrator, you know, my boy. Doré—yes, I knew him—he had bats in his belfry!”

And Mr. Whistler dismissed the subject by calling for a match, and then smoked his cigarette in grim silence, blowing the smoke through his nose.

Not liking a man, it is easy to shelve him by a joke, or to waive his work with a shrug and toss of the head, but not always will the ghost down at our bidding.

In the realm of art nothing is more strange than this: genius does not recognize genius. Still, the word is much abused, and the man who is a genius to some is never to others. In defining a genius it is easiest to work by the rule of elimination and show what he is not.

For instance, neither Reynolds, Landseer, nor Meissonier was a genius. These men were strong, sane, well poised—filled with energy and life. They were receptive and quick to grasp a suggestion or hint that could be turned to their advantage—to further the immediate plans they had in hand. They had ambition and the ability to concentrate on a thing and do it. Just what they focused their attention upon was largely a matter of accident. They had in them the capacity for success—they could have succeeded at anything they undertook, and they were too sensible to undertake a thing at which they could not succeed. They always saw light through at the other end.

I have success tied to the leg of my easel by a blue ribbon,

said Meissonier. They succeeded by mathematical calculation, and the fame, name, and gold they won was through a conscious laying hold upon the laws that bring these things to pass.

They chose to paint pictures, and the entire energy of their natures was concentrated upon this one thing. Practising the art, day after day, month after month, year after year, they acquired a wonderful facility. They knew the history of art—its failures, pitfalls, and successes.

They knew the human heart—they knew what the people wanted and what they didn’t. They set themselves to supply a demand. And all this keenness, combined with good taste and tireless energy, would have brought a like success in any one of a dozen different professions.

And these are the men who give plausibility to that stern half-truth: A man can succeed in anything he undertakes—it is all a matter of will.

But you cannot count Gustave Doré in any such category. He stands alone: he had no predecessors, and he left no successors. We say that the artist has his prototype; but every rule has its exception—even this one.

Gustave Doré drew pictures because he could do nothing else. He never had a lesson in his life, never drew from a model, could not sketch from nature; accepted no one’s advice; never retouched or considered his work after it was done; never cudgelled his brains for a subject; could read a book by turning the leaves; grasped all knowledge; knew all languages; found an immediate market for his wares and often earned a thousand dollars before breakfast; lived fifty years and produced over one hundred thousand sketches—an average of six a day; made two million dollars by the labor of his own hands; was knighted, flattered, proclaimed, adored, lauded, scorned, scoffed, hooted, maligned, and died broken-hearted.

Surely you cannot dispose of a man like this with a bon mot! Comets may be good or ill, but wise men make note of them, and the fact that they once flashed their blinding light upon us must live in the history of things that were.

An Alsatian by birth, and a Parisian by environment, Doré is spoken of as of the French School, but if ever an artist belonged to no “school ” it was Gustave Doré.

His early years were spent in Strasburg, within the shadow of the cathedral. His father was a civil engineer,—methodical, calculating, prosperous. The lad was the second of three sons: strong, bright, intelligent boys.

In his travels up and down the Rhine the father often took little Gustave with him, and the lad came to know each wild crag, and crowning fortress, and bend in the river where strong men with spears and bows and arrows used to lie in wait. In imagination Gustave repeopled the ruins and filled the weird forests with curious, haunting shapes. The Rhine reeks with history that merges off into misty song and fable; and this folk-lore of the storied river filled the day-dreams and night-dreams of this curious boy.

But all children have a vivid imagination, and the chief problem of modern education is how to conserve and direct it. As yet no scheme or plan or method has been devised that shows results, and the men of imagination seem to be those who have succeeded in spite of school. In Gustave Doré we have the curious spectacle of nature keeping bright and fresh in the man all those strange conceptions of the child, and multiplying them by a man’s strength.

The wild imaginings of Gustave only served his father and mother with food for laughter; and his erratic absurdities in making pictures supplied the neighbors’ fun. But actions that are funny in a child become disturbing in a man; he’s cute when little, but “sassy” when older. Gustave did not put away childish things.

When he had reached the age of indiscretion—was fourteen, and had a frog in his throat, and was conscious of being barefoot, he still imagined things and made pictures of them. His father was distressed and sought by bribes to get him to quit scrawling with pencil and turn his attention to logarithms and other useful things; but with only partial success.

When fifteen he accompanied his father and older brother to Paris where the older boy was to be installed in the École Polytechnique. It was the hope of the father that, once in Paris, Gustave would consent to remain with his brother, and thus, by a change of base, a reform in his tastes would come about and he would leave the Rhine with its foolish old-woman tales and cease the detestable habit of picturing them.

It was the first time Gustave had ever been to Paris—the first time he had ever visited a large city. He was fascinated, captivated, enthralled. Paris was fairy-land and paradise. He announced to his father and brother that he would not return to Alsace, neither would he go to the Polytechnique. They told him he must do either one or the other; and as the father was going back home in two days Gustave could have just forty-eight hours in which to decide his destiny.

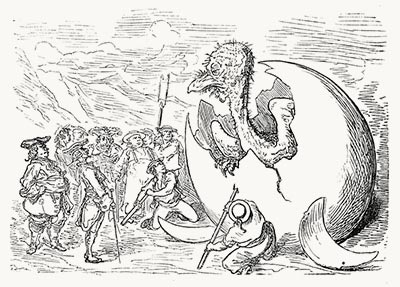

Passing by the office of the Journal pour Rire, the father and son gaping in all the windows like true rustics, they saw announced an illustrated edition of The Labors of Hercules. Some of the illustrations were shown in the window with the hope of tempting possible buyers. Gustave looked upon these illustrations with critical eye and his face flushed scarlet—but he said nothing.

He knew the book; aye, every tale in it, with all its possible variations, had long been to him a bit of true history. To him Hercules lived yesterday, and, confusing hearsay with memory, he was almost ready to swear that he was present and used a shovel when the strong man cleaned the Augean stables.

The next morning, when his father and brother were ready to go to visit the Polytechnique, Gustave pleaded illness and was allowed to lie abed. But no sooner was he alone than he seized pencil and paper and began to make pictures illustrating The Labors of Hercules. In two hours he had half a dozen pictures done, and fearing the return of his father he hurried with his pictures to monsieur Philipon, director of the Journal pour Rire. He shouldered past the attendants, pushed his way into the office of the great man, and spreading his pictures out on the desk cried, “Look here, sir! that is the way The Labors of Hercules should be illustrated!”

It was the action of one absorbed and lost in an idea. Had he taken thought he would have hesitated, been abashed, self-conscious—and probably been repulsed by the flunkeys before seeing monsieur Philipon. It was all the sublime effrontery and conceit—or naturalness, if you please—of a country bumpkin who did not know his place.

Philipon glanced at the pictures and then looked at the boy. Then he looked at the pictures. He called to another man in an adjoining room and they both looked at the pictures. Then they consulted in an undertone. It was suggested that the boy draw another illustration right there and then. They wished to make sure that he himself did the work, and they wanted to see how long it took. Gustave sat down and drew another picture.

Philipon refused to let the lad leave the office, and despatched a messenger for his father. When the father arrived, a contract was drawn up and signed, whereby it was provided that the “infant” should remain with Philipon for three years, on a yearly salary of five thousand francs, with the proviso that the lad should attend the school, Lycée Charlemagne, for four hours every day.

Thus, while yet a child, without discipline or the friendly instruction that wisdom might have lent, he was launched on the tossing tide of commercial life.

His Hercules was immediately published and made a most decided hit—a palpable hit. Paris wanted more, and Philipon wished to supply the demand. The new artist’s pictures in the Journal pour Rire boomed the circulation, and more illustrations were in demand. Philipon suggested that the four hours a day at school was unnecessary—Gustave knew more already than the teachers.

Gustave agreed with him, and his pay was doubled. More work rushed in, and Gustave illustrated serial after serial with ease and surety, giving to every picture a wildness and weirdness and awful comicality. The work was unlike anything ever before seen in Paris—everyone was saying, “What next!” and to add to the interest Philipon, from time to time, wrote articles for various publications concerning “the child illustrator” and "the artistic prodigy of the Journal pour Rire." With such an entree into life, how was it possible that he should ever become a master? His advantages were his disadvantages, and all of his faults sprang naturally as a result of his marvellous genius. He was the victim of facility.

Everything in this world happens because something else has happened before. Had the thing that happened first been different the thing that followed would not be what it is. Had Gustave Dore entered the art world of Paris in the conventional way, the master might have toned down his exuberance, taught him reserve, and gradually led him along until his tastes were formed and character developed. And then, when he had found his gait and come to know his strength, the name of Paul Gustave Doré might have stood out alone as a bright star in the firmament—the one truly great modern.

Or, on the other hand, would the ossified discipline and set rules of a school have shamed him into smirking mediocrity and reduced his native genius to neutral salts? Who dares say what would have occurred had not this happened and that first taken place?

Before Gustave Doré had been in Paris a year his father died. Shortly after, the Strasburg home was broken up, and madame Doré followed her son to Paris. Gustave’s tireless pencil was bringing him a better income than his father had ever made; and the mother and her three sons lived in comfort. The mother admonished Gustave to apply himself to pure art and not be influenced by Philipon and the others who were making fortunes by his genius. And this advice he intended to follow—not yet, but very soon.

There were Rabelais and Balzac’s Contes drolatiques to illustrate. These done, he would then enter the atelier of one of the masters and take his time in doing the highest work.

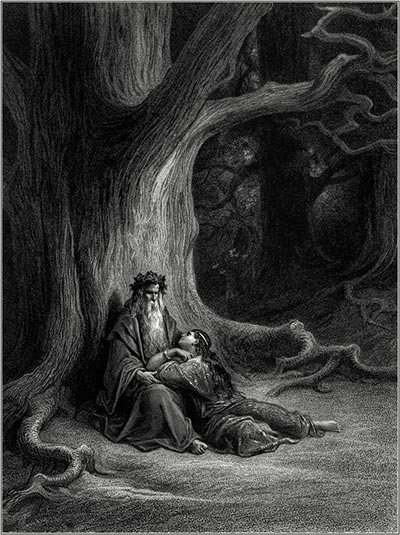

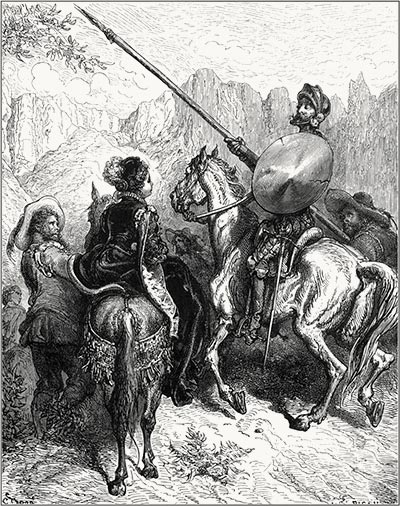

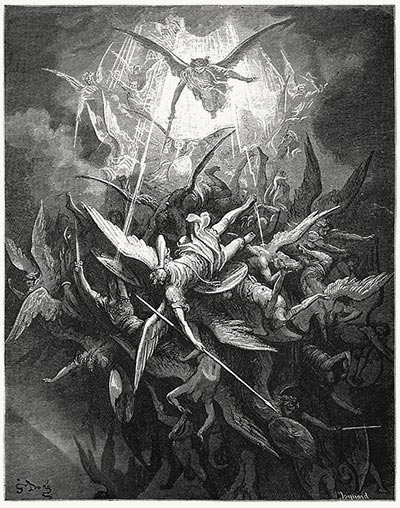

But before the books were done others came, with retainers in advance. Then a larger work was begun, to illustrate the Crimean War, in five hundred battle scenes. And so he worked—worked like a steam-engine—worked without ceasing. He illustrated Shakespeare’s Tempest as only Doré could; then Coleridge, Moore, Hood, Milton, Dante, Hugo, Gautier, and great plans were being laid to illustrate the Bible.

The years were slipping past. His brothers had found snug places in the army, and he and his mother lived together in affluence. Between them there was an affection that was very lover-like. They were comrades in everything—all of his hopes, plans, and ambitions were rehearsed to her. The love that he might have bestowed on a wife was reserved for his mother, and, fortunately, she had a mind strong enough to comprehend him.

In the corner of the large, sunny apartment that was set apart for his mother’s room, he partitioned off a little room for himself, where he slept on an iron cot. He wished to be near her, so each night he could tell her of what he had done during the day, and each morning rehearse his plans for the coming hours. By telling her, things shaped themselves, and as he described the pictures he would draw, others came to him.

The confessional seems a crying need of every human heart—we wish to tell someone. And without this confessional, where one soul can outpour to another that fully sympathizes and understands, marriage is a hollow, whited mockery, full of dead men’s bones.

There is a desire of the heart that makes us long to impart our joy to another. Corot once caught the sunset on his canvas as the great orb sank, a golden ball, behind the hills of Barbizon. He wished to show the picture to someone—to tell someone, and looking around saw only a cottage on the edge of the wood a quarter of a mile away, and thither he ran, crying to the astonished farmer, “I’ve got it! I’ve got it!”

When Doré did a particularly good piece of work, in the first intoxication of joy he would run home, kiss his mother on both cheeks, and picking her up in his strong arms run with her about the rooms.

At other times he would play leap-frog over the chairs, vault over the piano, and jump across the table. And this wild joy that comes after work well done he knew for many years. In the evening, after a particularly good day, he would play the violin and sing entire scenes from some opera, his mother turning the leaves.

As to his skill as a musician, is this testimonial on the back of a fine photograph I once had the pleasure of handling:

As a souvenir of tender friendship, presented to Gustave Doré, who joins with his genius as a painter the talents of a distinguished violinist and charming tenor. G. Rossini.

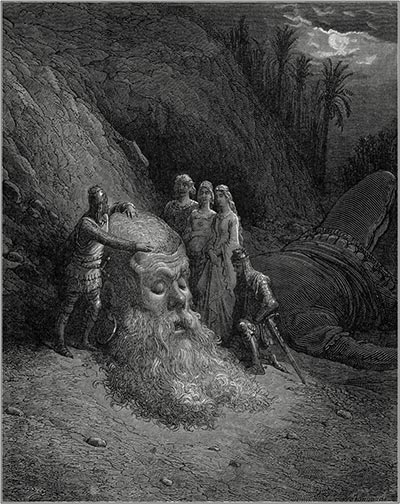

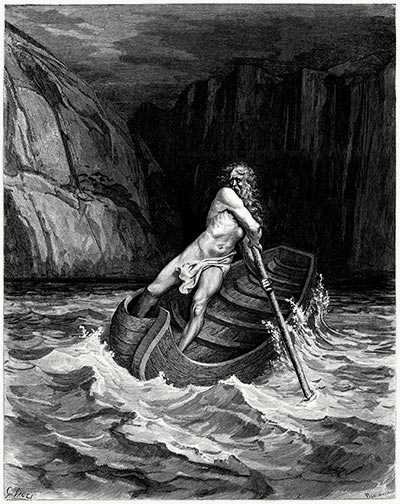

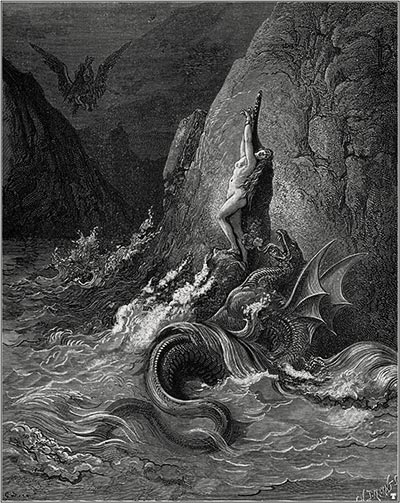

The illustrations for Dante’s Inferno were done in Doré’s twenty-second year, and for this work he was decorated with the Cross of the Legion of Honor. He never did better work, and at this time his hand and brain seemed at their best.

Every great writer and every great artist makes vigorous use of his childhood impressions. Childhood does not know it is storing up for the days to come, but its memories sink deep into the soul, and when called upon to express, the man reaches out and prints from the plates that are bitten deep; and these are either the pictures of his early youth—or else they tell of a time when he loved a woman.

The first named are the more reliable, for sex and love have been made forbidden subjects, until self-consciousness, affectation, and untruth creep easily into their accounting. All literature and all art are secondary sex manifestations, just as surely as the song of birds or the color and perfume of flowers are sex qualities. And so it happens that all art and all literature is a confession; and it occurs, too, that childhood does not stand out sharp and clear on memory’s chart until it is past and adolescence lies between. Then maturity gives back to the man the childhood that is gone forever.

Many of the world’s best specimens of literature are built on the impressions of childhood. Shakespeare, Victor Hugo, and I’ll name you another—James Whitcomb Riley—have written immortal books with the autobiography of childhood for both warp and woof

Gustave Dore’s best work is a reproduction of his childhood’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences—all well colored with the stuff that dreams are made of.

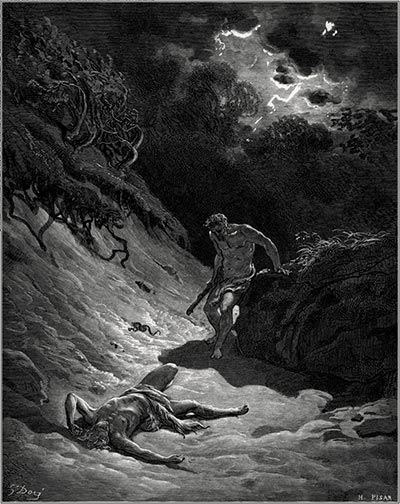

The background of every good Doré picture is a deep wood or mountain-pass or dark ravine. The wild, romantic passes of the Vosges, and the sullen crags, topped with dark mazes of wilderness, were ever in his mind, just as hesaw them yesterday when he clutched his father’s hand and held his breath to hear the singing of the wood-nymphs ‘mong the branches.

His tracery of bark and branch, and drooping bough held down with weight of dew, are startlingly true. The great roots of giant trees, denuded by storm and flood, lie exposed to view; and deep vistas are given of shadowy glade and swift-running mountain torrent. All is sombre, terrible, and tells of forces that tossed these mountain-tops like bowls, and of a Power immense, immeasurable, incomprehensible, eternal in the heavens.

Doré’s first exhibition in the Salon was made when he was eighteen, and a few years later, when he was presented with the Cross of the Legion of Honor, the decoration made his work exempt from jury examination. And so every year he sent some large painting to the Salon.

His work was the wonder of Paris, and on every hand his illustrations were in demand, but his canvases were too large in size and too terrible in subject to fit private residences. Patrons were cautious.

To own a “Doré” was proof of a high appreciation of art—or else a lack of it, buyers did not know which. They were afraid of being laughed at. His competitors began to hoot and jeer. Not being able to make pictures that would compete with his, they wrote him down in the magazines. His name became a jest.

Various of his illustrations for the Bible were enlarged into immense canvases, some of which were twenty feet long and twelve feet high. All who looked upon these pictures were amazed by the fecundity in invention and the skill shown in drawing; but the most telling criticism against them was their defect in coloring. Doré could draw but could not color, and the report was abroad that he was color-blind.

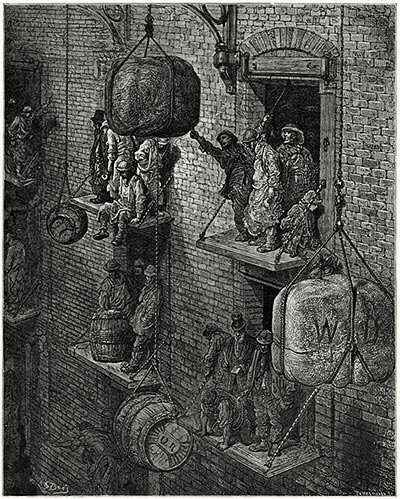

The only buyers for his pictures came from England and America. Paris loved art for art’s sake, and the Bible was not popular enough to make its illustration worth while. “What is this book you are working on?” asked a caller. It was different in London, where Spurgeon preached every Sunday to three thousand people. The “Dorés” taken to London attracted much attention—“mostly from the size of the canvases,” Parisians said. But the particular subject was the real attraction. Instead of reading their daily “chapter,” hard-working, tired people went to see a Doré Bible picture where it was exposed in some vacant storeroom and tuppence entrance fee charged.

It occurred to certain capitalists that if people would go to see one Doré why would not a Doré gallery pay? A company was formed, agents were sent to Paris and negotiations begun. Finally, on payment of three hundred thousand dollars, forty large canvases were secured, with a promise of more to come. Doré took the money, and, the agents being gone, ran home to tell his mother. She was at dinner with a little company of invited guests. Gustave vaulted over the piano, played leap-frog among the chairs, and turning a handspring across the table, incidentally sent his heels into a thousand-dollar chandelier that came toppling down, smashing every dish upon the table, and frightening the guests into hysterics. “It’s nothing”—said Madame Doré; “it ‘s nothing—Gustave has merely done a good day’s work!”

The Doré Gallery in London proved a great success. Spurgeon advised his flock to see it that they might the better comprehend Bible history; Rev. Dr. Parker spoke of the painter as one inspired by God;

Sunday-schools made excursions thither; men in hob nailed shoes knelt before the pictures, believing they were in the presence of a vision. And all these things were duly advertised, just as we have been told of the old soldier who visited the Gettysburg Cyclorama at Chicago and looking upon the picture, he suddenly cried to his companion, “Down, Bill, down! by t’ Lord, there ‘s a feller sightin’ his gun on us!”

Barnum offered the owners twice what they paid for the Doré Gallery, with intent to move the pictures to America, but they were too wise to accept. Twenty-eight of the canvases were eventually sold, however, for a sum greater than was paid for the lot, yet enough remained to make a most representative display; and no American in London misses seeing the Doré Gallery any more than we omit Madame Tussaud’s Wax Works.

In 1873, Doré visited England and was welcomed as a conquering hero. The Prince of Wales and the nobility generally paid him every honor. He was presented to the Queen, and Victoria thanked him for the great work he had done, and asked him to inscribe for her a copy of the “Doré Bible”.

More than this, the Queen directed that several Doré pictures be purchased and placed in Windsor Castle. Of course, all Paris knew of Doré’s success in England. Paris laughed. “What did I tell you?” said Berand. And Paris reasoned that what England and America gushed over must necessarily be very bad. The directors of the Salon made excuses for not hanging his pictures.

Doré had become rich, but his own Paris—the Paris that had been a foster mother to him, refused to accredit him the honor which he felt was his due. In 1878, smarting under the continued jibes and jeers of artistic France, he modelled a statue which he entitled Glory. It represents a woman holding fast in affectionate embrace a beautiful youth, whose name we are informed is Genius. The woman has in one hand a laurel wreath; hidden in the leaves of this wreath is a dagger with which she is about to deal the victim a fatal blow.

Doré grew dispirited, and in vain did his mother and near friends seek to rally him out of the despondency that was settling down upon him. They said, “You are only a little over forty, and many a good man has never been recognized at all until after that—see Millet!” But he shook his head.

When his mother died in 1881 it seemed to snap his last earthly tie. Of course he exaggerated the indifference there was towards him—he had many friends who loved him as a man and respected him as an artist.

But after the death of his mother he had nothing to live for, and thinking thus, he soon followed her. He died in 1883, aged fifty years.

This article was taken from Little Journey to the Homes of Eminent Painters written by Elbert Hubbard and published in New York and London by Putnam’s Sons, 1899.