Thomas Bewick

Though the art of cutting or engraving on wood is undoubtedly of high antiquity, as the Chinese and Indian modes of printing on paper, cotton, and silk, sufficiently prove; though, even in Europe, the art of engraving on blocks of wood may probably be traced higher than that of printing usually so called; and though, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, designs were executed of great beauty and accuracy, such as Holbein’s Dance of Death, the vignettes and head-letters of the early Missals and Bibles, and the engravings of flowers and shells in Gerard, Gesner, and Fuhschius; yet the bare inspection of these is sufficient to prove that their methods must have been very different from that which Bewick and his school have followed. The principal characteristic of the ancient masters is the crossing of the black lines, to produce or deepen the shade, commonly called cross-hatching. Whether this was done by employing different blocks, one after another, as in calico-printing and paper-staining, it may be difficult to say; but to produce them on the same block is so difficult and unnatural, that, though Nesbit, one of Bewick’s early pupils, attempted it on a few occasions, and the splendid print of Dentatus by Harvey shows that it is not impossible even on a large scale, yet the waste of time and labour is scarcely worth the effect produced.

To understand this, it may be necessary to state, for the information of those who may not have seen an engraved block of wood, that whereas the lines which are sunk by the graver on the surface of a copper-plate are the parts which receive the printing ink, which is first smeared over the whole plate, and the superfluous ink is scraped and rubbed off, that remaining in the lines being thus transferred upon the paper, by its being passed, together with the plate, through a rolling-press, the rest being left white — in the wooden block, all the parts which are intended to leave the paper white, are carefully scooped out with burins and gouges, and the lines and other parts of the surface of the block which are left prominent, after being inked, like types, with a ball or roller, are transferred to the paper by the common printing-press. The difficulty, therefore, of picking out, upon the wooden block, the minute squares or lozenges, which are formed by the mere intersection of the lines cut in the copper-plate, may easily be conceived.

The great advantage of wood-engraving is, that the thickness of the blocks (which are generally of boxwood, sawed across the grain) being carefully regulated by the height of the types with which they are to be used, are set up in the same page with the types; and only one operation is required to print the letter-press and the cut which is to illustrate it. The greater permanency, and indeed almost indestructibility,[1] of the wooden block, is besides secured; since it is not subjected to the scraping and rubbing, which so soon destroys the sharpness of the lines upon copper: and there is a harmony produced in the page, by the engraving and the letter-press being of the same colour; which is very seldom the case where copper-plate vignettes are introduced with letter-press.

It is difficult, perhaps impossible, to trace the history of wood-engraving, its early principles, the causes of its decay, etc, till its productions came to sink below contempt. But for its revival and present state we are unquestionably indebted to Bewick and his pupils.

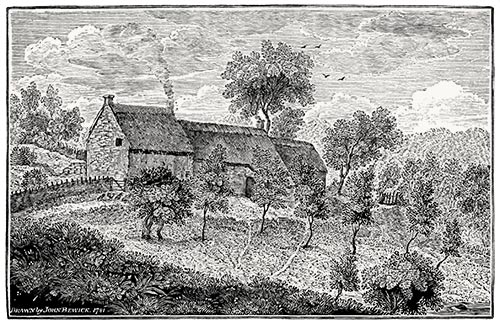

Thomas Bewick was born August 12, 1753, at Cherryburn, in the parish of Ovingham, and county of Northumberland. His father, John Bewick, had for many years a landsale colliery at Mickley-Bank, now in the possession of his son William. John Bewick, Thomas’s younger brother, and coadjutor with him in many of his works, was born in 1760 – unfortunately for the arts and for society, of which he was an ornament, died of a consumption, at the age of thirty-five.

The early propensity of Thomas to observe natural objects, and particularly the manners and habits of animals, and to endeavour to express them by drawing, in which, without tuition, he manifested great proficiency at an early age, determined his friends as to the choice of a profession for him. He was bound apprentice, at the age of fourteen, to Mr Ralph Beilby of Newcastle, a respectable copper-plate engraver, and very estimable man.[2] Mr Bewick might have had a master of greater eminence, but he could not have had one more anxious to encourage the rising talents of his pupil, to point out to him his peculiar line of excellence, and to enjoy without jealousy his merit and success, even when it appeared, in some respects, to throw himself into the shade. When Mr Charles Hutton, afterwards the eminent Professor Hutton of Woolwich, but then a schoolmaster in Newcastle, was preparing, in 1770, his great work on Mensuration, he applied to Mr Beilby to engrave on copper-plates the mathematical figures for the work. Mr Beilby judiciously advised that they should be cut on wood, in which case, each might accompany, on the same page, the proposition it was intended to illustrate. He employed his young apprentice to execute many of these; and the beauty and accuracy with which they were finished, led Mr Beilby to advise him strongly to devote his chief attention to the improvement of this long-lost art. Several mathematical works were supplied, about this time, with very beautiful diagrams; particularly Dr Enfield’s translation of Rossignol’s Elements of Geometry.

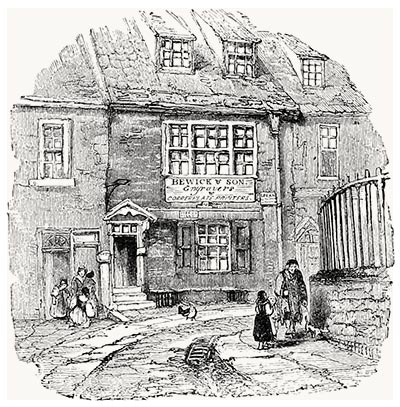

On the expiration of his apprenticeship, he visited the metropolis for a few months, and was, during this short period, employed by an engraver in the vicinity of Hatton-Garden. But London, with all its gaieties and temptations, had no attractions for Bewick: he panted for the enjoyment of his native air, and for indulgence in his accustomed rural habits. On his return to the North, he spent a short time in Scotland, and afterwards became his old master’s partner, while John, his brother, was taken as their joint-apprentice.

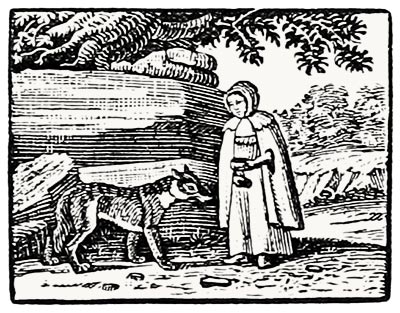

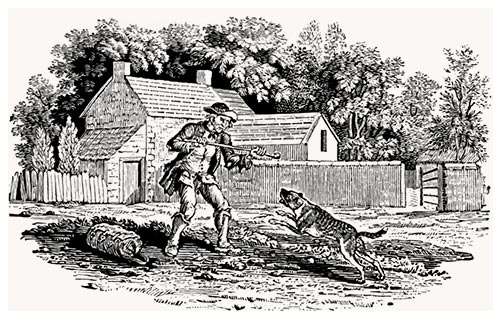

About this time, Mr Thomas Saint, the printer of the Newcastle Courant, projected an edition of Gay’s Fables, and the Bewicks were engaged to furnish the cuts. One of these, The Old Hound, obtained the premium of the Society of Arts, for the best specimen of wood-engraving, in 1775. An impression of this may be seen in the Memoir pre-fixed to Select Fables, printed for Charnley, Newcastle, in 1820; from which many notices in the present Memoir are taken. Mr Saint, in 1776, published also a work entitled, Select Fables, with an indifferent set of cuts, probably by some inferior artist; but in 1779 came out a new edition of Gay, and, in 1784, of the Select Fables, with an entire new set of cuts, by the Bewicks.

It has been already said, that Thomas Bewick, from his earliest youth, was a close observer and accurate delineator of the forms and habits of animals; and, during his apprenticeship, and indeed throughout his whole life, he neglected no opportunity of visiting and drawing such foreign animals as were exhibited in the different itinerant collections which occasionally visited Newcastle. This led to the project of the History of Quadrupeds; a Prospectus of which work, accompanied by specimens of several of the best cuts then engraved, was printed and circulated in 1787; but it was not till 1790 that the work appeared.

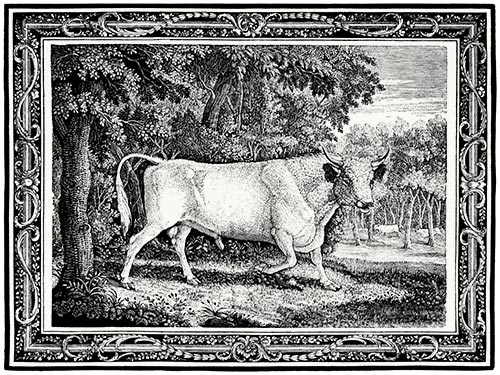

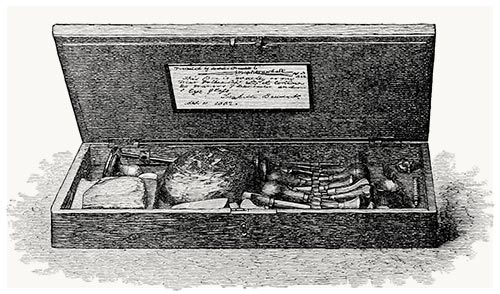

In the mean time, the Prospectus had the effect of introducing the spirited undertaker to the notice of many ardent cultivators of natural science, particularly of Marmaduke Tunstall, Esq. of Wycliffe, whose museum was even then remarkable for the extent of its treasures, and for the skill with which they had been preserved; whose collection also of living animals, both winged and quadruped, was very considerable. Mr Bewick was invited to visit Wycliffe, and made drawings of various specimens, living and dead, which contributed greatly to enrich his subsequent publications. The portraits which he took with him of the wild cattle in Chillingham Park, the seat of the Earl of Tankerville (whose agent, Mr John Bailey, was also an eminent naturalist, and very intimate friend of Mr Bewick), particularly attracted Mr Tunstall’s attention; and he was very urgent to obtain a representation, upon a larger scale than was contemplated for his projected work, of those now unique specimens of the ancient Caledonian breed. For this purpose, Mr Bewick made a special visit to Chillingham, and the result was the largest wood-cut he ever engraved; which, though it is considered as his chef d’œuvre, seemed, in its consequences, to shew the limits within which wood-engraving should generally be confined. The block, after a few impressions had been taken off, split into several pieces, and remained so till, in the year 1817, the richly figured border having been removed, the pieces containing the figure of the wild bull were so firmly clamped together, as to bear the force of the press; and impressions may still be had. A few proof-impressions on thin vellum of the original block, with the figured border, have sold as high as twenty guineas.

As it obviously required much time, as well as labour, to collect, from various quarters, the materials for a General History of Quadrupeds, it is evident that much must have been done in other ways, in the regular course of ordinary business. In a country engraver’s office, much of this requires no record; but, during this interval, three works on copper seem to have been executed, chiefly by Mr Thomas Bewick. A small quarto volume, entitled, A Tour through Sweden, Lapland, etc, by Matthew Consett. Esq., accompanied by Sir G. H. Liddell, was illustrated with engravings by Beilby and Bewick, the latter executing all those relating to natural history, particularly the reindeer and their Lapland keepers, brought over by Sir H. Liddell, whom he had thus the unexpected opportunity of delineating from the life. During this interval, he also drew and engraved on copper, at the expense of their respective proprietors, The Whitley large Ox, belonging to Mr Edward Hall, the four quarters of which weighed 187 stone; and The remarkable Kyloe Ox, bred in Mull by Donald Campbell, Esq. and fed by Mr Robert Spearman of Rothley Park, Northumberland. This latter is a very curious specimen of copper-plate engraving, combining the styles of wood and copper, particularly in the minute manner in which the verdure is executed.

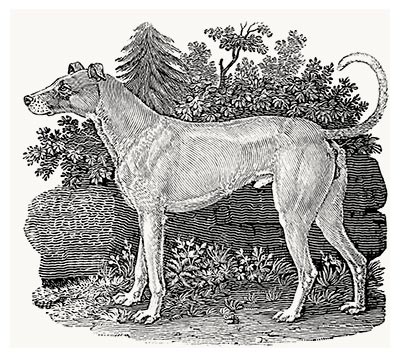

At length appeared The General History of Quadrupeds, a work uncommonly well received by the public, and ever since held in increased estimation. Perhaps there never was a work to which the rising generation of the day was, and no doubt that for many years to come will be, under such obligations, for exciting in them a taste for the natural history of animals. The representations which are given of the various tribes, possess a boldness of design, a correctness of outline, an exactness of attitude, and a discrimination of general character, which convey, at the first glance, a just and lively idea of each different animal. The figures were accompanied by a clear and concise statement of the nature, habits, and disposition of each animal: these were chiefly drawn up by his able coadjutors, Mr Beilby, his partner, and his printer Mr Solomon Hodgson; subject, no doubt, to the corrections and additions of Mr Bewick. In drawing up these descriptions, it was the endeavour of the publishers to lay before their readers a particular account of the quadrupeds of our own country, especially of those which have so materially contributed to its strength, prosperity, and happiness, and to notice the improvements which an enlarged system of agriculture, supported by a noble spirit of generous emulation, has diffused throughout the country.

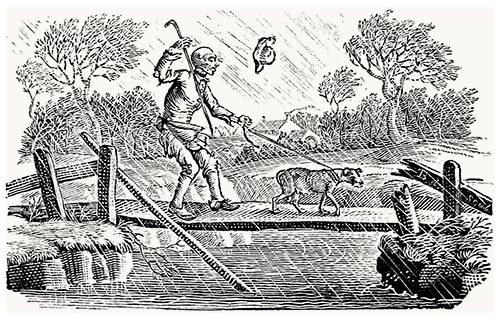

But the great and, to the public in general, unexpected, charm of the History of Quadrupeds, was the number and variety of the vignettes and tailpieces, with which the whole volume is embellished. Many of these are connected with the manners and habits of the animals near which they are placed; others are, in some other way, connected with them, as being intended to convey to those who avail themselves of their labours, some salutary moral lesson, as to their humane treatment; or to expose, by perhaps the most cutting possible satire, the cruelty of those who ill-treat them. But a great proportion of them express, in a way of dry humour peculiar to himself, the artist’s particular notions of men and things, the passing events of the day, etc. etc.; and exhibit often such ludicrous, and, in a few instances, such serious and even awful, combinations of ideas, as could not perhaps have been developed so forcibly in any other way.

From the moment of the publication of this volume, the fame of Thomas Bewick was established on a foundation not to be shaken. It has passed through seven large editions, with continually growing improvements.

It was observed before, that Mr Bewick’s younger brother, John, was apprenticed to Mr Beilby and himself. He naturally followed the line of engraving so successfully struck out by his brother. At the close of his apprenticeship, he removed to London, where he soon became very eminent as a wood-engraver; indeed, in some respects, he might be said to excel the elder Bewick.

This naturally induced Mr William Bulmer, the spirited proprietor of the Shakspeare Press, himself a Newcastle man, to conceive the desire of giving to the world a complete specimen of the improved arts of type and block-printing; and for this purpose he engaged the Messrs Bewicks, two of his earliest acquaintances, to engrave a set of cuts to embellish the poems of Goldsmith, The Traveller and Deserted Village, and Parnell’s Hermit. These appeared in 1795, in a royal quarto volume, and attracted a great share of public attention, from the beauty of the printing and the novelty of the embellishments, which were executed with the greatest care and skill, after designs made from the most interesting passages of the poems, and were universally allowed to exceed every thing of the kind that had been produced before. Indeed, it was conceived almost impossible that such delicate effects could be obtained from blocks of wood; and it is said that his late Majesty (George III.) entertained so great a doubt upon the subject, that he ordered his bookseller, Mr G. Nicol, to procure the blocks from Mr Bulmer, that he might convince himself of the fact.

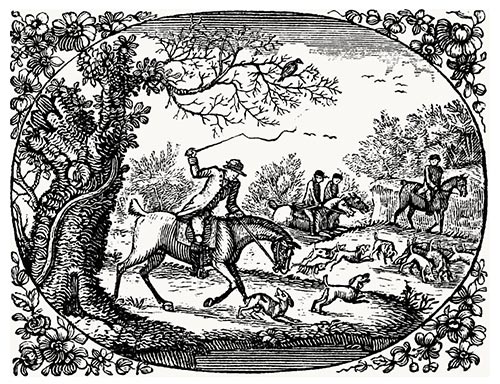

The success of this volume induced Mr Bulmer to print, in the same way, Somerville’s Chase. The subjects which ornament this work being entirely composed of landscape scenery and animals, were peculiarly adapted to display the beauties of wood engraving. Unfortunately for the arts, it was the last work of the younger Bewick, who died at the close of 1795, of a pulmonary complaint, probably contracted by too great application. He is justly described in the monumental inscription in Ovingham churchyard, as only excelled as to his ingenuity as an artist by his conduct as a man.

Previously, however, to his death, he had drawn the whole of the designs for the Chase on the blocks, except one; and the whole were beautifully engraved by his brother Thomas.

In 1797, Messrs Beilby and Bewick published the first volume of the History of British Birds, comprising the land-birds. This work contains an account of the various feathered tribes, either constantly residing in, or occasionally visiting, our islands. While Bewick was engraving the cuts (almost all faithfully delineated from nature), Mr Beilby was engaged in furnishing the written descriptions. Some unlucky misunderstandings having arisen about the appropriation of this part of the work, a separation of interests took place between the parties, and the compilation and completion of the second volume, Water-birds, devolved on Mr Bewick alone – subject, however, to the literary corrections of the Rev. Henry Cotes, Vicar of Bedlington. In the whole of this work, the drawings are minutely accurate, and express the natural delicacy of feather, down, and accompanying foliage, in a manner particularly happy. And the variety of vignettes and tailpieces, and the genius and humour displayed in the whole of them (illustrating, besides, in a manner never before attempted, the habits of the birds), stamps a value on the work superior to the former publication on Quadrupeds.[3] This also has passed through many editions, with and without the letterpress.

Mr Bewick’s next works were on a larger scale: four very spirited and accurate representations of a zebra, an elephant, a lion, and a tiger, from the collection and for the use of Mr Pidcock, the celebrated exhibitor of wild beasts. A few impressions were taken of each of these, which are now very scarce.

In 1818, he published a collection of fables, entitled, The Fables of Æsop and others, with Designs by T. Bewick. This work has not, however, been received by the public with so much favour.

In 1820, Mr Emerson Charnley, bookseller in Newcastle, having purchased of Messrs Wilson of York a large collection of woodcuts, which had been engraved by the Bewicks in early life, for various works printed by Saint, conceived the design of employing them in the illustration of a volume of Select Fables (already referred to). Though aware that Mr Bewick wished it to be fully understood that he had no wish to feed the whimsies of bibliomanists,

as he himself expressed it, and perhaps was a little jealous of all the imperfections of his youth being set before the public, yet the Editor conceived that he was rendering to the curious in wood engraving a very acceptable service, by thus rescuing from oblivion so many valuable specimens of the early talents of the revivors of this elegant art. They were thus enabled to study the gradual advance towards excellence of these ingenious artists, from their very earliest beginnings, and to trace the promise of talents at length so conspicuously developed.

Mr Bewick, however, was also engaged from time to time, by himself and his pupils, in furnishing embellishments to various other works, which it is now impossible to particularize. One may be mentioned, Dr Thornton’s Medical Botany But as he had himself no knowledge of this department of natural science, the cuts engraved for this work were merely servile copies of the drawings sent, executed with great exactness indeed, but not at all con amore. It is believed that the work itself obtained very little of the public attention.

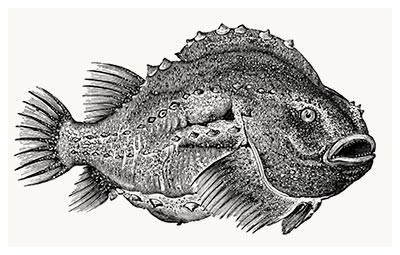

Several of the later years of Mr Bewick’s life were, in part at least, devoted to a work on British Fishes. A number of very accurate drawings were made by himself, and more by his son Robert, whose accuracy in delineation is perhaps equal to his father’s. From twenty to thirty of these had been actually engraved, and a very large proportion (amounting to more than a hundred) of vignettes, consisting of river and coast scenery, the humours of fishermen and fishwomen, the exploits of birds of prey in fish-taking, etc. It was hoped that his son would have gone on with and completed the work, but in this the public have been disappointed; and now that Mr Yarrell’s beautiful work is completed, it possibly might not answer.

Mr Bewick had a continued succession of pupils, many of whom have done the highest honour to their preceptor; and some are carrying the art to a stage of advancement, at which he himself had the candour to acknowledge, on the inspection of Northcote’s Fables, he had never conceived that it would arrive. It is almost needless to mention the names of Nesbit and Harvey. Others were cut off by death, or still more lamentable circumstances, who would otherwise have done great credit to their master; as Johnson, whose premature death occurred in Scotland, while copying some of the pictures of Lord Breadalbane, Clennel, Ranson – Hole, whose exquisite vignette in the title-page of Mr Shepherd’s Poggio gave the highest promise, was stopped in a more agreeable way, by succeeding to a handsome fortune.

The last project of Mr Bewick was, to improve at once the taste and morals of the lower classes, particularly in the country, by a series of blocks on a large scale, to supersede the wretched, sometimes immoral, daubs with which the walls of cottages are too frequently clothed. A cut of an Old Horse, intended to head an Address on Cruelty to that noble animal, was his last production: the proof of it was brought to him from the press only three days before he died.

It may be observed, that, in the works of the early masters, in the art of wood engraving, there was little more attempted than a bold outline. It remained for the burine of Bewick to produce a more complete and finished effect, by displaying a variety of tints, and producing a perspective, in a way that astonished even the copperplate engravers, by slightly lowering the surface of the block where the distance or lighter parts were to be shewn. This was first suggested by his early acquaintance Bulmer, who, during the period of their joint apprenticeship, invariably took off, at his master’s office, proof-impressions of Bewick’s blocks. He particularly printed for his friend the engraving of the Huntsman and Old Hound, which, as has been already observed, obtained for the young artist the premium from the Society of Arts.

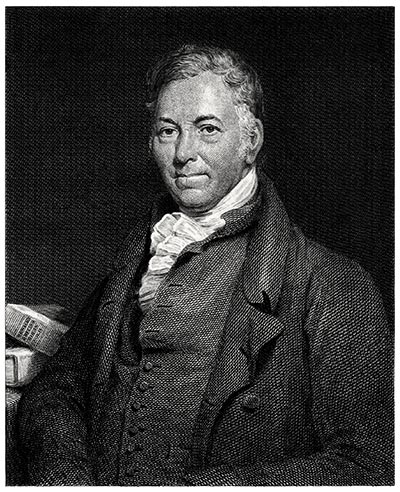

Mr Bewick was in person robust, well formed and healthy. He was fond of early rising, walking, and indulging in all the rustic and athletic sports so prevalent in the north of England. Many portraits of him have been engraved and published; but the only full-length portrait of him was executed by Nicholson, and engraved by his pupil Ranson.[4] It was afterwards proposed by a select number of bis friends and admirers, to have a bust of him executed in marble, as a lasting memorial of the high regard they entertained for his genius and excellent character. The bust was executed by Baily with great fidelity and taste; and was presented, by the subscribers, to the Council and Members of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle, and now occupies a situation in the most prominent part of the spacious library room of that useful Institution.

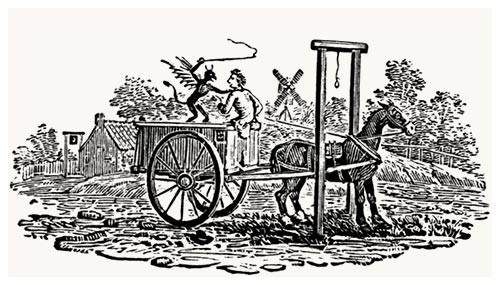

Many anecdotes are current among his friends concerning the occasions of many of his vignettes. Among others, one is told of a person, who had for many years supplied him with coals, being convicted of defrauding him in measure, on which occasion he sent him a letter of rebuke for his ingratitude and dishonesty. At the bottom of the letter, he sketched with his pen the figure of a man in a coal cart, accompanied by a representation of the devil close by his side, who is stopping the vehicle immediately under a gallows, beneath which was written, The End and Punishment of All Dishonest Men. This well-timed satire so affected the nervous system of the poor delinquent, that he immediately confessed his guilt, and on his knees implored his pardon. This small sketch was afterwards adopted as a tail-piece, which may be seen in the first volume of the British Birds, p. 110. (First Edition).[5]

Mr Bewick was a man of warm attachments, particularly to the younger branches of his family. It is known that, during his apprenticeship, he seldom failed to visit his parents once a week at Cherryburn, distant about fourteen miles from Newcastle; and when the Tyne was so swelled with rain and land floods, that he could not get across, it was his practice to shout over to them, and, having made inquiries after the state of their health, to return home.

In 1825, in a letter to an old crony in London, after describing with a kind of enthusiastic pleasure the domestic comforts which he daily enjoyed, he says, I might fill you a sheet in dwelling on the merits of my young folks, without being a bit afraid of any remarks that might be made upon me, such as ‘look at the old fool, he thinks there’s nobody has sic bairns as he has.’ In short, my son and three daughters do all in their power to make their parents happy.

Mr Bewick was naturally of the most persevering and industrious habits. The number of blocks he has engraved is almost incredible. At his bench he worked and whistled with the most perfect good humour, from morn to night, and ever and anon thought the day too short for the extension of his labours. He did not mix much with the world, for he possessed a singular and most independent mind. In the evening, indeed, when the work of the day was finished, he generally retired to a neighbouring public house, to smoke his pipe, and drink his glass of porter with an old friend or two, who knew his haunt, and enjoyed the naïveté and originality of his remarks. But he luxuriated in the bosom of his family; and no pleasures he could enjoy in the latter stage of his life, were equal in his esteem to the sterling comforts of his own fireside.

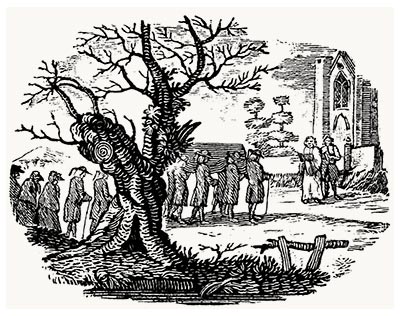

He died, as he had lived, an upright and truly honest man; and breathed his last after a short illness, in the midst of his affectionate and disconsolate offspring, at his residence in West Street, Gateshead, on Saturday November 8. 1828 in the 76th year of his age. His remains were accompanied by a numerous train of friends, to the family burial place at Ovingham, and deposited along with his parents, his wife (who had died February 1. 1826, aged 72), and his brother previously mentioned.[6]

Much more might be said of this distinguished artist. More has been said. In Blackwood’s Magazine (for 1825), there is a very elegant critique upon Mr Bewick’s works.[7] In the first volume of the Transactions of the Natural History Society of Newcastle, p. 132, is a Memoir of Mr Bewick, by George Clayton Atkinson, Esq., whose love of nature led him, while very young, to seek the acquaintance of our native artist, who was always ready to encourage rising merit. But amidst much judicious remark, there is a detail of particular conversations, etc. which, though highly interesting in this particular neighbourhood, would probably not be so to the public at large. In the third volume of Audubon’s Ornithological Biography, p. 300, an account of his interviews with Mr Bewick, during his residence in Newcastle, forms one of those delightful Episodes with which he contrives to enliven his accounts of birds. We have taken the liberty of quoting it.

Through the kindness of Mr Selby of Twizel-House in Northumberland, I had anticipated the pleasure of forming an acquaintance with the celebrated and estimable Bewick, whose works indicate an era in the history of the art of engraving on wood. In my progress southward, after leaving Edinburgh in 1827, I reached Newcastle-upon-Tyne about the middle of April, when Nature had begun to decorate anew the rich country around. The lark was in full song, the blackbird rioted in the exuberance of joy, the husbandman cheerily plied his healthful labours, and I, although a stranger in a foreign land, felt delighted with all around me, for I had formed friends who were courteous and kind, and whose favour I had reason to hope would continue. Nor have I been disappointed in my expectations.

Bewick must have heard of my arrival at Newcastle before I had an opportunity of calling upon him, for he sent me by his son the following note: – ‘T. Bewick’s compliments to Mr Audubon, and will be glad of the honour of his company this day to tea at six o’clock.’ These few words at once proved to me the kindness of his nature, and, as my labours were closed for the day, I accompanied the son to his father’s house.

As yet I had seen but little of the town, and had never crossed the Tyne. The first remarkable object that attracted my notice was a fine church, which my companion informed me was that of St. Nicholas. Passing over the river by a stone bridge of several arches, I saw by the wharfs a considerable number of vessels, among which I distinguished some of American construction. The shores on either side were pleasant, the undulated ground being ornamented with buildings, windmills, and glass-works. On the water glided, or were swept along by great oars, boats of singular form, deeply laden with the subterranean produce of the hills around.

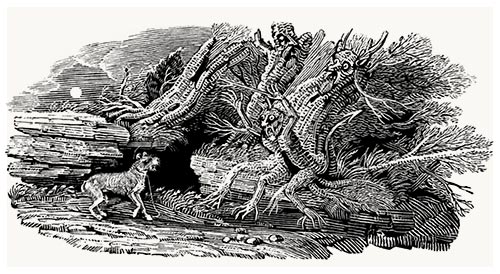

At length we reached the dwelling of the engraver, and I was at once shewn to his workshop. There I met the old man, who, coming towards me, welcomed me with a hearty shake of the hand, and for a moment took off a cotton night-cap, somewhat soiled by the smoke of the place. He was a tall stout man, with a large head, and with eyes placed farther apart than those of any man that I have ever seen: – a perfect old Englishman, full of life, although seventy-four years of age, active and prompt in his labours. Presently he proposed shewing me the work he was at, and went on with his tools. It was a small vignette, cut on a block of boxwood not more than three by two inches in surface, and represented a dog frightened at night by what he fancied to be living objects, but which were actually roots and branches of trees, rocks, and other objects bearing the semblance of men. This curious piece of art, like all his works, was exquisite, and more than once did I feel strongly tempted to ask a rejected bit, but was prevented by his inviting me up stairs, where, he said, I should soon meet all the best artists of Newcastle.

There I was introduced to the Misses Bewick, amiable and affable ladies, who manifested all anxiety to render my visit agreeable. Among the visitors. I saw a Mr Good, and was highly pleased with one of the productions of his pencil, a full-length miniature in oil of Bewick, well drawn, and highly finished.

The old gentleman and I stuck to each other, he talking of my drawings, I of his woodcuts. Now and then he would take off his cap, and draw up his grey worsted stockings to his nether clothes; but whenever our conversation became animated, the replaced cap was left sticking as if by magic to the hind part of his head, the neglected hose resumed their downward tendency, his fine eyes sparkled, and he delivered his sentiments with a freedom and vivacity which afforded me great pleasure. He said he had heard that my drawings had been exhibited in Liverpool, and felt great anxiety to see some of them, which he proposed to gratify by visiting me early next morning along with his daughters and a few friends. Recollecting at that moment how desirous my sons, then in Kentucky, were to have a copy of his works on Quadrupeds, I asked him where I could procure one, when he immediately answered ‘here,’ and forthwith presented me with a beautiful set.

The tea-drinking having in due time come to an end, young Bewick, to amuse me, brought a bagpipe of a new construction, called the Durham Pipe, and played some simple Scotch, English, and Irish airs, all sweet and pleasing to my taste. I could scarcely understand how, with his large fingers, he managed to cover each hole separately. The instrument sounded somewhat like a hautboy, and had none of the shrill warlike notes or booming sound of the Highland bagpipe. The company dispersed at an early hour, and when I parted from Bewick that night, I parted from a friend.

A few days after this I received another note from him, which I read hastily, having with me at the moment many persons examining my drawings. This note having, as I understood it, intimated his desire that I should go and dine with him that day. I accordingly went; but judge of my surprise when, on arriving at his house at 5 o’clock, with an appetite becoming the occasion, I discovered that I had been invited to tea and not to dinner. However, the mistake was speedily cleared up to the satisfaction of all parties, and an abundant supply of eatables was placed on the table. The Reverend William Turner joined us, and the evening passed delightfully. At first our conversation was desultory and multifarious, but when the table was removed, Bewick took his seat at the fire, and we talked of our more immediate concerns. In due time we took leave, and returned to our homes, pleased with each other and with our host.

Having been invited the previous evening to breakfast with Bewick at 8, I revisited him at that hour, on the 16th April, and found the whole family so kind and attentive that I felt quite at home. The good gentleman, after breakfast, soon betook himself to his labours, and began to shew me, as he laughingly said, how easy it was to cut wood; but I soon saw that cutting wood in his style and manner was no joke, although to him it seemed indeed easy. His delicate and beautiful tools were all made by himself, and I may with truth say that his shop was the only artist’s ‘shop’ that I ever found perfectly clean and tidy. In the course of the day Bewick called upon me again, and put down his name on my list of subscribers in behalf of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle. In this, however, his enthusiasm had misled him, for the learned body for which he took upon himself to act, did not think proper to ratify the compact.

Another invitation having come to me from Gatehead, I found my good friend seated in his usual place. His countenance seemed to me to beam with pleasure as he shook my hand. ‘I could not bear the idea,’ said he, ‘of your going off, without telling you, in written words, what I think of your Birds of America. Here it is in black and white, and make of it what use you may, if it be of use at all.’ I put the unsealed letter in my pocket, and we chatted on subjects connected with natural history. Now and then he would start and exclaim, ‘Oh, that I were young again! I would go to America too. Hey! what a country it will be, Mr Audubon.’ I retorted by exclaiming, ‘Hey! what a country it is already, Mr Bewick!’ In the midst of our conversation on birds and other animals, he drank my health and the peace of all the world in hot brandy toddy, and I returned the compliment, wishing, no doubt, in accordance with his own sentiments, the health of all our enemies. His daughters enjoyed the scene, and remarked, that, for years, their father had not been in such a flow of spirits.

I regret that I have not by me at present the letter which this generous and worthy man gave me that evening, otherwise, for his sake, I should have presented you with it. It is in careful keeping, however, as a memorial of a man whose memory is dear to me; and be assured I regard it with quite as much pleasure as a manuscript ‘Synopsis of the Birds of America,’ by Alexander Wilson, which this celebrated individual gave to me at Louisville in Kentucky, more than twenty years ago. Bewick’s letter, however, will be presented to you along with many others, in connection with some strange facts, which I hope may be useful to the world. We protracted our conversation much beyond our usual time of retiring to rest, and at his earnest request, and much to my satisfaction, I promised to spend the next evening with him, as it was to be my last at Newcastle for some time.

On the 19th of the same month I paid him my last visit, at his house. When we parted, he repeated three times, ‘God preserve you, God bless you!’ He must have been sensible of the emotion which I felt, and which he must have read in my looks, although I refrained from speaking on the occasion.

A few weeks previous to the death of this fervent admirer of nature, he and his daughters paid me a visit to London. He looked as well as when I had seen him at Newcastle. Our interview was short but agreeable, and when he bade adieu, I was certainly far from thinking that it might be the last. But so it was, for only a very short time had elapsed when I saw his death announced in the newspapers.

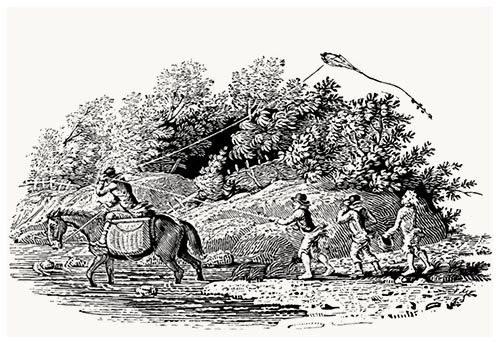

My opinion of this remarkable man is, that he was purely a son of nature, to whom alone he owed nearly all that characterized him as an artist and a man. Warm in his affections, of deep feeling, and possessed of a vigorous imagination, with correct and penetrating observation, he needed little extraneous aid to make him what he became, the first engraver on wood that England has produced. Look at his tail-pieces, Reader, and say if you ever saw so much life represented before, from the glutton who precedes the Great Black-backed Gull, to the youngsters flying their kite, the disappointed sportsman who, by shooting a magpie, has lost a woodcock, the horse endeavouring to reach the water, the bull roaring near the style, or the poor beggar attacked by the rich man’s mastiff. As you turn each successive leaf, from beginning to end of his admirable books, scenes calculated to excite your admiration everywhere present themselves. Assuredly you will agree with me in thinking that in his peculiar path none has equalled him. There may be men now, or some may in after years appear, whose works may in some respects rival or even excel his, but not the less must Thomas Bewick of Newcastle-on-Tyne be considered in the art of engraving on wood what Linnaeus will ever be in natural history, though not the founder, yet the enlightened improver and illustrious promoter.

This article was taken from Natural History of Parrots written by Prideaux John Selby and published in Edinburgh, London, and dublin, 1836. It was printed as a preamble under the title: "Memoir of Thomas Bewick; eminent engraver on wood".

- ^ Many of Mr Bewick’s blocks have printed upwards of 300,000: the head-piece of the Newcastle Courant above a million; and a small vignette for a capital letter in the Newcastle Chronicle, during a period of twenty years, at least two millions.

- ^ It is stated by the author of The Pursuit of Knowledge under Difficulties, forming a part of the Library of Entertaining Knowledge (we know not on what authority, but we think it probable,) that he was in the habit of exercising his genius by covering the walls and doors of his native village with sketches in chalk of his favourites of the lower creation with great accuracy and spirit; and that some of these performances chancing to attract Mr Beilby’s notice, as he was passing through Cherryburn, he was so much struck with the talent which they displayed, that he immediately sought out the young artist, and obtained his father’s permission to take him with him as his apprentice.

^ “Of Bewick’s powers, the most extraordinary is the perfect accuracy with which he seizes and transfers to paper the natural objects which it is his delight to draw. His landscapes are absolute facsimiles; his animals are whole-length portraits. Other books on natural history have fine engravings; but still, neither beast nor bird in them have any character; dogs and deer, lark and sparrow, have all airs and countenances marvellously insipid, and of a most flat similitude. You may buy dear books, but if you want to know what a bird or quadruped is, to Bewick you must go at last. It needs only to glance at the works of Bewick, to convince ourselves with what wonderful felicity the very countenance and air of his animals are marked and distinguished. There is the grave owl, the silly wavering lapwing, the pert jay, the impudent over-fed sparrow, the airy lark, the sleepy-headed gourmand duck, the restless titmouse, the insignificant wren, the clean harmless gull, the keen rapacious kite – every one has his character.

“His vignettes are just as remarkable. Take his British Birds, and in the tailpieces to these volumes you shall find the most touching representations of Nature in all her forms, animate and inanimate. There are the poachers tracking a hare in the snow; and the urchins who have accomplished the creation of a snow-man; the disappointed beggar leaving the gate open for the pigs and poultry to march over the good dame’s linen, which she is laying out to dry; the thief who sees devils in every bush – a sketch that Hogarth himself might envy; the strayed infant standing at the horse’s heels, and pulling his tail, while the mother is in an agony flying over the style; the sportsman who has slipped into the torrent; the blind man and boy, unconscious of Keep on this side; and that best of burlesques on military pomp, the four urchins astride of gravestones for horses, the first blowing a glass trumpet, and the others bedizened in tatters, with rush-caps and wooden swords.

“Nor must we pass over his seaside sketches, all inimitable. The cutter chasing the smuggler – is it not evident that they are going at the rate of at least ten knots an hour? The tired gulls sitting on the waves, every curled head of which seems big with mischief. What pruning of plumage, what stalkings, and flappings, and scratchings of the sand, are depicted in that collection of sea-birds on the shore! What desolation is there in that sketch of coast after a storm, with the solitary rock, the ebb-tide, the crab just venturing out, and the mast of the sunken vessel standing up through the treacherous waters! What truth and minute nature is in that tide coming in, each wave rolling higher than its predecessor, like a line of conquerors, and pouring in amidst the rocks with increased aggression! And, last and best, there are his fishing scenes. What angler’s heart but beats whenever the pool-fisher, deep in the water, his rod bending almost double with the rush of some tremendous trout or heavy salmon? Who does not recognize his boyish days in the fellow with the set rods, sheltering himself from the soaking rain behind an old tree? What fisher has not seen yon old codger, sitting by the river side, peering over his tackle, and putting on a brandling?

“Bewick’s landscapes, too, are on the same principle with his animals: they are for the most part portraits, the result of the keenest and most accurate observation. You perceive every stone and bunch of grass has had actual existence: his moors are north-country moors, the progeny of Cheviot, Rimside, Simonside, or Carter. The tailpiece of the old man pointing out to his boy an ancient monumental stone, reminds one of the Millfield plain, or Flodden Field. Having only delineated that in which he himself has taken delight, we may deduce his character from his pictures: his heartfelt love of his native country, its scenery, its manners, its airs, its men and women; his propensity

by himself to wander

Adown some trotting burn’s meander,

And no thinks lang:his intense observation of nature and human life; his satirical and somewhat coarse humour; his fondness for maxims and old saws; his vein of worldly prudence now and then cropping out, as the miners call it, into daylight; his passion for the seaside, and his delight in the angler’s solitary trade: All this, and more, the admirer of Bewick may deduce from his sketches.” – Blackwood’s Magazine, p. 2, 3.

- ^ In 1823, James Ramsay made a small full-length watercolor study, from which F. Bacon took a well-known engraving.

- ^ In page 82 of the same volume is the representation of a cart-horse running away with some affrighted boys, who had got into the cart while the careless driver was drinking in a hedge-alehouse. It is observable, that the rapidity of the cart is finely expressed by the almost total disappearance of the spokes of the wheel; a circumstance, it is believed, never before noticed by an artist.

- ^ There is an affecting tail-piece (the final one in his Fables, 1820), in which he describes The End of All, representing his own funeral, with a view of the west end of Ovingham church, and the two family monuments fixed in the wall. And it may be interesting also to notice, as a proof of that family-attachment mentioned in p. 36, that the tail-piece in p. 162 of his Fables bears the date of his mother’s, and that in p. 176 of his father’s death.

- ^ For an extract from which, see Note 3.

- Illustration sources:

The Internet Archive (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8)