Anne Emond

Anne was born in 1982, she is a recent graduate from the School of Visual Arts. She has participated in a couple of group exhibitions, and her work has been published in TimeOut New York. Anne has just started working as a freelance illustrator and she’s willing to take commissions.

Old Book Illustrations: You define yourself not only as an illustrator, but also as a writer, and you do indeed like telling stories: many of your drawings, for instance, belong to narrative series. They usually depict a world that is familiar, similar to our everyday world, but somewhat skewed to give way to slightly melancholy or disturbing feelings. Are those feelings easier to express through several drawings rather than in a standalone illustration? Or is there something more fulfilling in following a character through a number of situations?

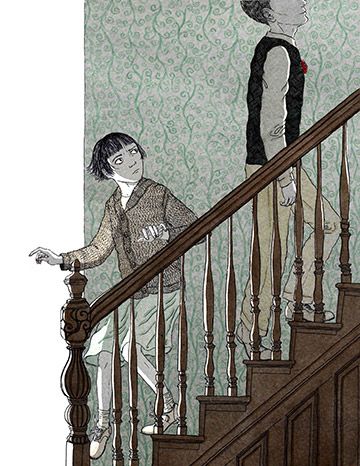

Anne Emond – While I’m always impressed by the power of a single image to convey a complex moment or emotion, what’s really appealing to me about illustration more than anything else is the creation and development of characters, which is generally best achieved in a narrative series. My interest in this type of illustration probably stems from the fact that I spent most of my childhood up through the end of college writing stories and always thought that I would be a writer.

Even in the illustration that I loved when I was younger, like the wonderful New Yorker cartoons by artists like Helen Hokinson and Mary Petty, the artists would often follow their same stock characters through different magazine issues, so these single panels ended up being something of a continuous narrative.

When I started drawing more devotedly after college it was a natural progression that I’d go from writing stories to illustrating them. Then I kind of discovered comics, and realized that my goal from then on would be to find a way of naturally incorporating my love of writing with my love of drawing.

In my two years in the illustration program at SVA my main projects were to write and illustrate two short novels. In terms of the slight melancholy, that’s usually the emotion that drives me to start a story or do a drawing, which is probably why most of my drawings have that sensibility about it. If I’m in a really buoyant mood I don’t usually want to draw or write, I’d rather spend time with people.

Visit Anne Emond on the Web:

Her portfolio

Her blog

Or

Contact her

OBI: While you’re still aspiring to achieve a more flowing and looser quality in your ink work, you seem to have found the approach that is right for you: the use of simple, bare lines with an ornamental bent, accurate but not rigidly scrupulous anatomy and perspective – all things that lend a touch of both sophistication and seeming naivety to your drawings. In comparison, you appear to be still in a more experimenting phase with colouring and texturing techniques, as though your choices in that area were not quite so settled. Is this due to strict technical concerns, like the necessity to try out various effects, palettes, etc, or are you still sometimes hesitating on the part that colour should play in your illustrations?

A. E. – I actually only started using color about a year ago; before that I was pretty much strictly pen and ink, with few exceptions. So I’ve been teaching myself to use color but it’s been a long, slow process. I started by collecting images of other people’s art where I liked how color had been used, everything from contemporary illustrators to Japanese woodblock prints to film stills and so on. When it came time to color in my own black and white drawing, I would choose one of those images I’d collected and literally just copy the colors into my own drawing with watercolor. After awhile I grew more confident and didn’t need to use as much reference.

In terms of the medium I chose watercolor because many of the illustrators I admire use it, and it is fairly versatile but can be extremely sophisticated. It took a few months for me to actually grasp how difficult watercolor is to use, and to comprehend how unforgiving it is. You can’t erase your mistakes which makes it much more infuriating than gouache or acrylic, but that’s also why watercolor has such a light and spontaneous quality. But I have a seriously long way to go.

The biggest lesson I’ve had to learn though was raised by a guest critic in one of my classes last year. The illustrator Istvan Banyai was examining a color drawing by one of my classmates. He said that it looked like she had done the black and white portion of the drawing without thinking about the color. That was a pretty major realization for me because that’s how I had been working up until then. Now I know that if a drawing is going to be successful, when it is done in black and white it should feel incomplete until the color is added, and that certain elements (like possibly shadow or depth) that could be expressed with pen and ink should be left out so that the color can come in and do some of the work.

OBI: You seem to draw inspiration from many different directions: not only do you mention many artists, but they come from the most varied spheres of artistic activity. We naturally find among them illustrators, like Edward Gorey and Arthur Rackham, ancient masters like Peter de Hooch, modern ones like Duchamp, but also film directors, traditional Asian artists, and the list goes on. Does this curiosity, which also makes you run to museums and libraries, have something to do with your former years as a student majoring in art history? And does the training you received then have an influence on how you look at other artist’s work, and in the way you are able to use it as an inspiration for yourself?

A. E. – I think there’s no doubt that studying art history gave me a really nice basic foundation for appreciating many different kinds of art and provided me with a good vocabulary for describing why I like the art that I do.

In terms of being a working artist, I think what I learned from studying art history is two-fold. Firstly, it made me realize that if you’re working in a certain art form, be it comics or illustration or photography or whatever, it is essential that you understand and are knowledgeable about the history of your art form, your contemporaries and your predecessors and the theories and practices that drove them. Nobody works in a vacuum, all the greats did it, Picasso was constantly referencing Rembrandt and so on. Obviously there are exceptions but I think that artists who don’t have that kind of intellectual curiosity are going to ultimately produce pretty mediocre work.

But something else I learned is that when you are working in a particular art form, it is a mistake to only expect to be influenced by the other people who are doing what you do. Like for example if you are a comic book artist and only concern yourself with the work of comic book artists, and believe that the Dutch masters with their often incredibly hilarious and symbol-laden narrative paintings have nothing to teach you.

OBI: The thesis project that kept you busy for several months was based on the model of a typical children’s book, combining text and illustrations. Before that, you had tried your hand at comics, and if we are to believe your blog, you still retained a keen interest in that sort of illustrated narrative only a few months ago. Could going back to comics writing and drawing be one of your projects for a not-so-far future? or would you rather explore more traditional sorts of illustrations a little longer?

A. E. – I really admire the discipline required for making comics, their kind of weird outsider/low art status, frankly the entire culture that surrounds them and their sometimes sordid history. I took three or four graphic novel classes, devoured dozens of mini-comics and graphic novels, read up extensively on the craft of the form (Will Eisner’s Comics & Sequential Art, and two of Scott McCloud’s books, among others), and went to see lectures and panels featuring pretty much every graphic novelist under the sun.

Eventually I realized that I would never be very good at drawing comics unless I took a great deal of care and patience when actually plotting out a story in comic book form. The most innovative and exciting comics are very concerned with and conscious about creative ways of framing and telling the story, really using the medium of the comic to its greatest effect in sometimes very witty and self-referential ways.

This is how it should be, but the problem is that I’m too impatient to work that way. Also my fairly detailed style doesn’t necessarily serve comics well. It has been said before that in comics the eye needs a chance to rest, a good comic won’t just have ten beautiful detailed panels in a row one after the other, you need to provide a break somehow, some variation. Which is why I’ve been dabbling in illustrated novels; I can give the eye a rest from each detailed illustration by dividing them with three or four pages of text. Ultimately I find writing a ton of text gives me a lot more pleasure than the painstaking process of plotting out a comic.

While I often get a bit dewy-eyed when I look at all the amazing comics being produced these days and it’s possible that I’ll one day try my hand at it again, I think it’s unlikely that it’s something I’ll ever excel at.

More interviews from the Present Tense section »

All the pictures included in this article are copyrighted to Anne Emond.

If you would like to be the illustrator featured in this section, please read our guidelines.